Worldbuilding, First Drafts and Fishing…

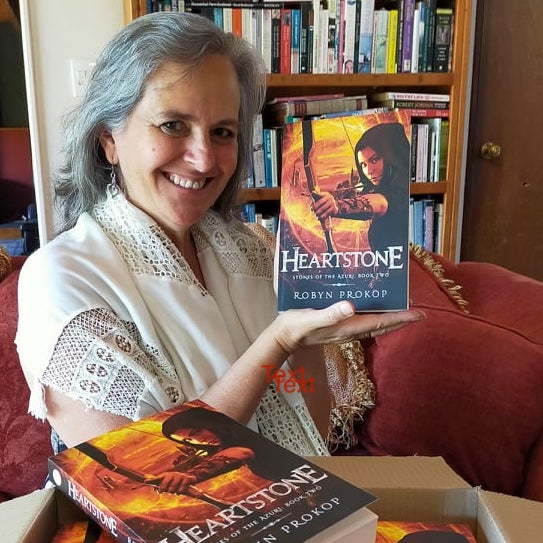

Last week I finally got my hands on a physical copy of my latest book, Heartstone. Once again, it was a strange and exhilarating feeling. Up until that moment, even though Book Two had existed as an ebook since December and my family overseas had sent photos of their paperback versions, some part of me still did not quite believe that it was real.

There is just something so evocative about a physical book: the satin touch of the cover, the inky coastlines of the map, the smell of the new pages. When you’ve written that book yourself, there’s an added fascination of realising that your ideas, once so ethereal and uncertain, have been captured in physical form. Having existed only in sketches, scattered thoughts, Pinterest boards, Scrivener files and scruffy drafts, Heartstone is now most definitely a book. The map is set in ink and the second part of Ash and Kep’s epic adventure is safely in the hands of readers.

So, with the heady mixture of excitement and trepidation that always accompanies first drafts, I’m now turning my attention to the completion of Book Three: Darkstone. As I embark on this next stage of the journey, I can’t help but reflect on the weird and wonderful process of writing a book.

Many writers have tried to describe their creative process through metaphor. Some say writing is like building a bird’s nest, others liken it to chiseling away at a stone sculpture or even driving a car at night: “You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” (E. L. Doctorow) Ernest Hemmingway famously quipped: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

Bleeding aside, the variety of metaphors used to describe the writing process only seems to confirm something that I have long suspected: different minds probably work in very different ways.

Personally, I rather like Virginia Woolf’s association of writing with fishing. Both activities are addictive, require significant reserves of patience, and involve an element of surprise. As with fishing, you never really know what you are going to catch when you attempt to haul up ideas from your own subconscious: an ‘old boot’ silted up with clichés; the shining silver of a fresh idea; or just a string of tiddlers that need throwing back for another day.

Catching a glimpse of a promising storyline or character arc is very much like seeing the flash of a fish in the water. Sometimes you need to let it circle for a while, watching until it takes shape. Then, at some point you need to strike, hoping and praying that the idea won’t slip the hook before it is safely landed. From there things become rather like a wrestling bout with an octopus. First drafts are dreadfully slippery beasts. They have a tendency to shed tentacles which, without warning, can take on a life of their own, filling your boat with all manner of wriggling distractions.

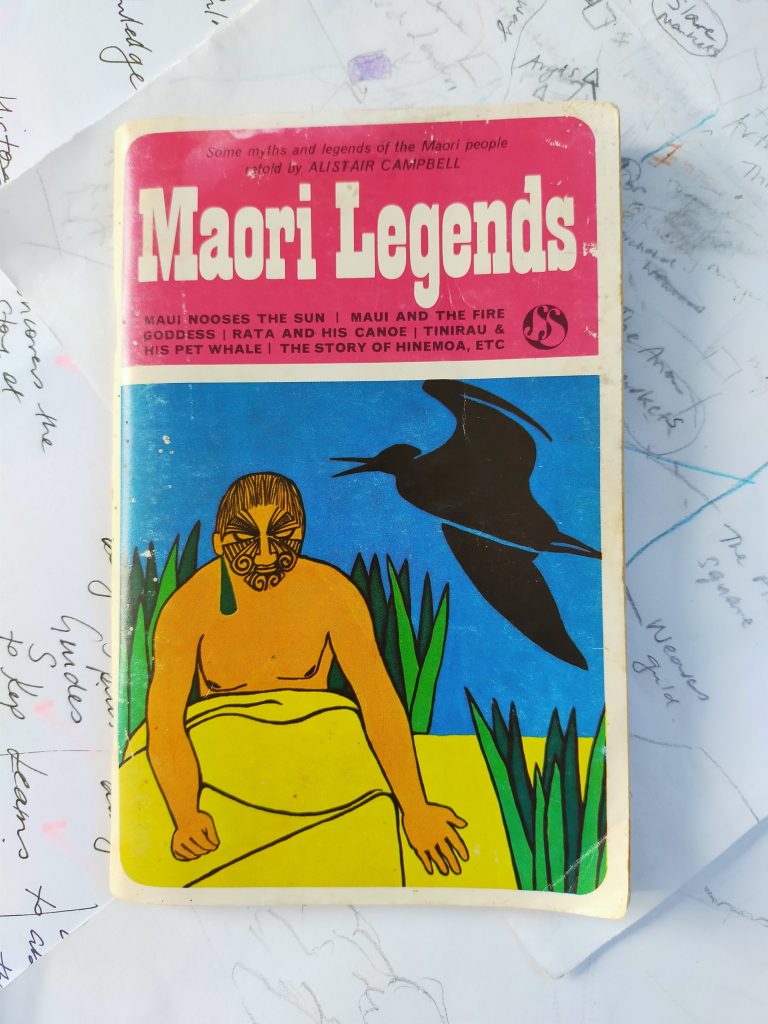

For writers of Epic Fantasy, this (now quite ridiculously extended) fishing metaphor seems especially apt, since it is our business to fish up entire new worlds from the depths of imagination. As a New Zealander, I grew up with the Maori legend of Maui, which might explain why I’m so drawn to this particular analogy. One of Maui’s many fabulous exploits was to fish up the North Island using a magical jawbone stolen from his grandmother. As a little girl, I adored stories about Maui — I’m sure I had a bit of a crush on him. Maui was right up there with Zorro and Pippi Longstocking.

When I was about nine years old, I was given a book of Maori legends, written by Alistar Campbell. For some reason I carried that little volume with me all around the world — somehow, it just kept finding its way into my suitcase. I still have it today and Maui still has a special place in my heart. Maybe it’s because Maui is not just any old hero: he is also a trickster, and I love a trickster. You could argue that the best writers are tricksters themselves. If you’ve read the first two Stones of the Azuri books, then you’re bound to recognise the trickster archetype in my character of Sarin.

An early sketch of Ash, looking very worried indeed.

Initial concept for the warriors’ silver bands

Sadly, the first draft of any story is nothing like the shining image of the perfect idea that swims through the mind at night, or leaps up in a tantalising flash by day. Oh no. First drafts are sorry, misshapen affairs that feel as if they’ve been hacked at by Maui’s brothers. I’m always very relieved to move past those ugly beginnings and begin the process of shaping and refining: the delightful challenge of polishing up the good stuff, shedding all the rubbish and adding in fun details.

Kep’s token

Of course once you’ve created your fantasy world, the crucial question becomes how much to reveal to readers. In the end, much of the thinking and painstaking planning that goes into worldbuilding and back stories must remain below the surface: readers only need to see enough to understand the characters and story, anything else can become a distraction. It’s a careful balancing act, making sure that readers have enough information to be able to make the leap from peak to peak without getting bogged down by unnecessary description and detail. As Scott Lynch puts it: “The real question in worldbuilding is not how much can I dump on the page, but how much can I get away with not actually telling people?”

The Malshorne’s hut

The arch at Mildaresh

World-building is not just static research, the homework that must be done before you write the book. Rather it is a highly dynamic process. The map for T’al Agria was only finalised in the week that Heartstone was sent for formatting — I was still shifting islands, renaming towns and mulling over whether or not to show trade routes. As is the case in our own world, everything in a fantasy world is interconnected: politics, history, religion, economics, art, culture and environment. The slightest changes in character and plot can cause major tremors in the story world, sometimes enough to raise mountains.

Rough map of Mildaresh

Not only that, the story itself has peaks and troughs, and pits of despair that the characters must drag themselves out of in order to triumph. Particularly pesky are those minor characters who have a habit of taking on a life of their own and demanding their own story arcs. Ultimately, it is this constant interplay between character, narrative and context which shapes fantasy worlds. And that’s what makes it fun. Then, just to complicate matters further, add some magic. Fantasy worlds all involve magic of some sort, and whatever magic system the author comes up with has to be compatible with the logic of the world.

Fishing up a fantasy world from the depths of your imagination is not the hardest part. The greater challenge lies in making that world sit still and behave itself. I confess that I used to grow impatient with some of my favourite authors for taking so long to produce the next book in the series. Now that I better understand the thrashing, messy business of writing a novel, all is forgiven. The book you hold in your hand is merely the part that sits above the surface, after the waters have settled. In a way, all books are strange miracles, wrestled into existence from an endless sea of possibilities.